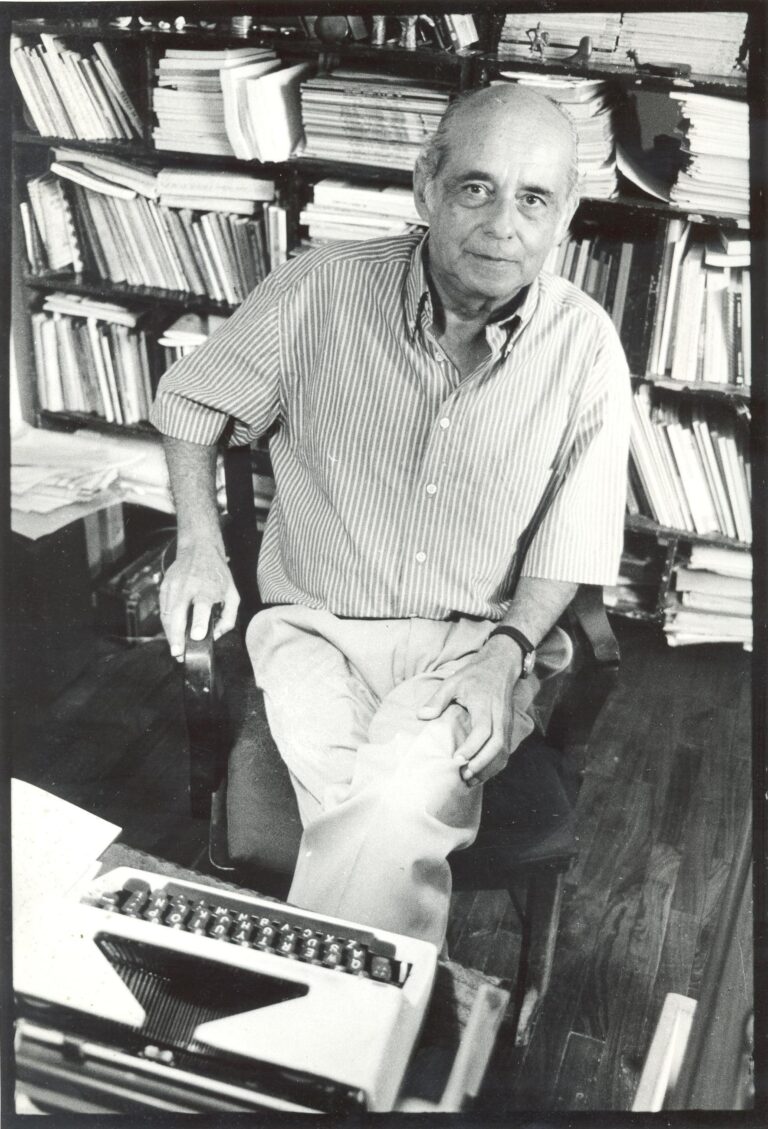

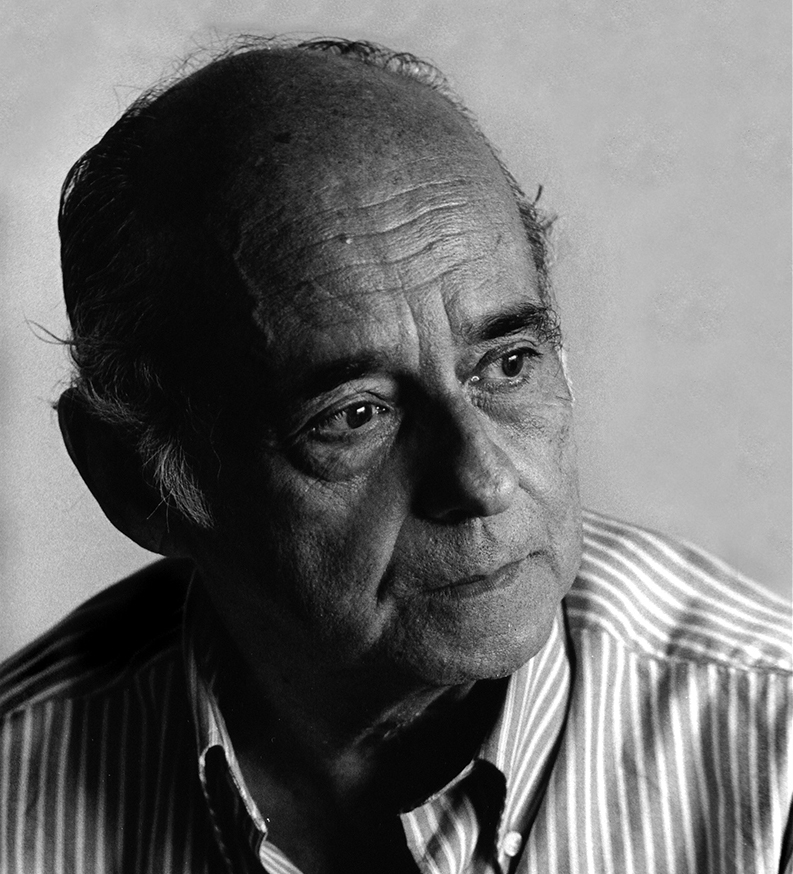

Carlos Germán Belli was born in Lima on 15 September 1927. As a child, he lived for two years in Amsterdam and later studied at the Colegio Raimondi (Raimondi School). He entered the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos and the Pontificia Universidad Católica, but did not pursue an academic career, as he began working in the public administration at a very young age, and later in journalism. In 1958, he published his first book: Poemas (Poems), to be followed by, among other titles, iOh Hada Cibernética! (iOh Cybernetic Fairy) (1961), El pie sobre el cuello (The Foot on the Neck) (1967), Por el monte abajo (Down the Hill) (1966), Sextinas y otros poemas (Sextinas and Other Poems) (1970), En alabanza del bolo alimentario (In Praise of the Food Bolus) (1979), Los talleres del tiempo (The Workshop of Time) (1992), iSalve, Spes! (2003), Los versos juntos. Poesía Completa (Verses together. Complete Poetry) (2008). Considered one of the most important poets in the language, Belli has been awarded the National Poetry Prize (1962), the Ibero-American Poetry Prize Pablo Neruda (2006), and the Casa de las Américas Poetry Prize José Lezama (2009) and has been nominated for the Cervantes Prize and the Queen Sofia Prize for Ibero-American Poetry. He has also twice been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship (1969 and 1987). In 1980, he graduated as a doctor in Literature from the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos with a thesis on the poetry of Carlos Oquendo de Amat and in 1982; he was inducted into the Peruvian Academy of Language. In 2014, the poet Carlos Germán Belli was invited by The Centro Cultural Inca Garcilaso of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to inaugurate the cycle “La República de los poetas. Antología viva de la poesía peruana, 2014-2021“ (The Republic of Poets. Living Anthology of Peruvian Poetry, 2014-2021), which was accompanied by a bibliographic exhibition on his work.

Conjunto de versos que ofrecen, según el propio autor, dos corrientes: la preocupación por las formas clásicas, algunos poemas de métrica clásica y, por otro lado, la vanguardia, el espíritu moderno.

La cibernética, en el año 60, no es más que una palabra que se atribuye al ordenamiento de información sobre el hombre, pero es en la escritura del poeta donde alcanza un nuevo orden, luz, y destino. Carlos Germán Belli creerá lo que el hada le permita, esta diosa cibernética que todos los cuerpos portamos pero que de manera tan secretamente guardamos como ignorantes de nuestros propios dioses.

Este inédito libro nos muestra un sujeto contento de sí mismo, dedicado a escribir y amar “en el restante tiempo terrenal”. En esta, su última etapa creadora, nos sigue sorprendiendo con sus ríspidos versos (¿ríspidos, surrealistas, barrocos?) y su afán de fundar un futuro con un lenguaje que se arraigue en la tradición, más allá de cualquier ominoso signo de postergación y alineación.

Recopilación de crónicas periodísticas.

El hablante poético, sin más ni más, da a entender desde el título del libro (El alternado paso de los hados) que él es un juguete del destino, según suele decirse comúnmente. Y lo hace verificando el cambiante discurrir de los hados.

En este poemario el lector encontrará las primeras prosas líricas que aparecieron como palabras preliminares, codas y secciones independientes.

Carlos Germán Belli (1927) is a separate case in Spanish-language poetry. Without background or disciples, since he discovered poetry while still in school and reading Rubén Darío, according to his own confession, he has followed a personal path as a poet, creating, as Borges says, his own precursors and constructing a work of an insolent and surprising nature, which, over the years, has been recognised as one of the most profound and original of our time.

This recognition has taken time because the poetry of Belli is not easy, nor does it make concessions to readers, rather it challenges and induces them, in order to understand and enjoy it, to revise the most elementary notions of what, in the most general sense of those words, is understood by poetry and by beauty.

Everything is disconcerting in this work, starting with its sources, so dissimilar. In it surrealism, lyricism and the currents of the so-called avant-garde have left a mark on it, as have the great poets of the Golden Age and classics such as Petrarch. But no less important in giving it its being have been the slang of Lima and the slang sayings and proverbs which in the poems of Belli are often confused with the most elaborate cultism and archaisms in images, metaphors and allegories as unexpected as truculent.

All this would seem to indicate that the poetry of Belli is formalist and experimental, a search for novelties and boldness in the domain of the word, rhythm, stanza and verse. And, in fact, it is also so, but only in the second instance, because, in truth, this poetry of so worked and singular expression, so exquisitely mannerist, is impregnated with experiences, passion and suffering, it is a dramatic testimony of daily life and frustrations, miseries, disappointments, chimeras and petty occurrences, which the poet exhibits with as much impudence as anguish, dressing them up in luxurious clothing, like a dilapidated, toothless and purulent old woman wrapped in layers of ermine and luxury jewellery.

All that is grotesque in the formidable contrasts of Carlos Germán Belli is made is humanized by humour, another constant in his poetic world. An acid humour sometimes and other belligerent and fierce, a humour that makes laugh and alarm us at the same time, and that leads us to reflect on all that is for the poet matter of laughter and mockery: the human condition, transcendence, freedom, destiny, time, old age, death and solitude. I know of no poet in our language who embodies better than Carlos Germán Belli what André Breton described as “humor negro” (black humour) in his famous anthology.

In the poems of Belli a zebra licks the mutilated thigh of a girl, two food bowls converse in the “estómago laico” (secular stomach) of the poet and wonder where they go; the same poet, who is a poor amanuensis from Peru, he dismantling “hasta los cachas de cansado ya” (up to his hindquarters with fatigue), and there is a place called “El Bofedal” (The Bofedal) (where all the human beings who, like the poet, feel that this is a world of desolation and ruin will be thrown out. Not surprisingly, the foetus that is about to break into this horrible world gathers its forehead and raises its eyebrows in horror at such a prospect. When he grows up and assumes his despicable human destiny, he will undoubtedly end up worshipping the Cybernetic Fairy as well, that strange grotesque fetish which, from an early age, officiates in poetry of Belli poetry as goddess and godmother, as artificial and baroque, as macabre and absurd as that stupefied, misguided and suffering humanity which has made it its divinity.

The pessimism that transpires in the poetry of Carlos Germán Belli is both historical and metaphysical. It has to do with social conditions, which multiply injustice, inequality, abuse and frustration, and with existence itself, a condition that abdicates human beings to a destiny of pain and failure. Now, if this voice to lead itself so abjectly, and to mourn complains and protests, and sometimes seems to enjoy it as a masochist, were just that, pure despair, perpetual tearing, it would hardly awaken the spell and adhesion that good poetry always deserves. And that is the case with the poetry of Belli, which, when the reader learns to decipher its clues and penetrates its labyrinths, reveals the treasures hidden beneath those weeping, despairing masks: an immense tenderness, a deep-rooted pity for the moral and material misery of those who suffer and are unable to resist the onslaught of a life they do not understand, which shakes them and knocks them down like a cyclonic wind or a sudden tidal wave. Pity, humanity, solidarity with those who suffer, from the same suffering, under the tinsel and wailing, a heart that bleeds, drop by drop, and makes its own the pain that permeates the world: that is what the poetry of Belli represents.

I say “representa” (represents) in the theatrical sense of the word. Because the poetry of Belli is also spectacle. And we have seen some of the bizarre, grotesque and pathetic characters who star in this macabre comedy: they are just a sample of the motley crowd of grotesques, human and non-human, who parade through this caricature and fantastic universe.

However, like pessimism, what is funambulist and farce about this blackly humorous nightmare in the poetic word of Belli is humanised by the purity of feeling that gives this strange comedy its authenticity, its suggestive force and its truth. It is a playful and circus-like world, but the poet does not play with it, or, in any case, plays with the seriousness with which someone bets his life, risking everything he has and is in that game of life and death.

I began to read Belli when he published his first poems, back in the fifties, in the magazine Mercurio Peruano, and it was enough for me to read those half dozen texts to feel that this was a new voice, of powerful lyrical solvency and great imaginative audacity, capable – as only the great poets know – of producing those transformations that consist of making beautiful the ugly, stimulating the sad and the golden – that is, poetry – what touches. Everything that Carlos Germán Belli has written since then has only confirmed and enriched his extraordinary gift for poetry.

Oh Hada Cibernética

cuándo harás que los huesos de mis manos

se muevan alegremente

para escribir al fin lo que yo desee

a la hora que me venga en gana

y los encajes de mis órganos secretos

tengan facciones sosegadas

en las últimas horas del día

mientras la sangre circule como un bálsamo a lo largo de mi cuerpo

Yo, mamá, mis dos hermanos

y muchos peruanitos

abrimos un hueco hondo, hondo

donde nos guarecemos,

porque arriba todo tiene dueño,

todo está cerrado con llave,

sellado firmemente,

porque arriba todo tiene reserva:

la sombra del árbol, las flores,

los frutos, el techo, las ruedas,

el agua, los lápices,

y optamos por hundirnos

en el fondo de la tierra,

más abajo que nunca,

lejos, muy lejos de los jefes,

hoy domingo,

lejos, muy lejos de los dueños, entre las patas de los animalitos, porque arriba

hay algunos que manejan todo,

que escriben, que cantan, que bailan, que hablan hermosamente,

y nosotros, rojos de vergüenza,

tan sólo deseamos desparecer

en pedacititos.

¡Oh alimenticio bolo, mas de polvo!, ¿quién os ha formado?

Y todo se remonta a la tenue relación entre la muerte y el huracán,

que estriba en que la muerte alisa el contenido de los cuerpos,

y el huracán los lugares

donde residen los cuerpos,

y que después convierten juntamente y ensalivan

tanto los cuerpos como los lugares, en un inmenso y raro

alimenticio bolo, mas de polvo.

¡Oh Hada Cibernética!, ya líbranos

con tu eléctrico seso y casto antídoto,

de los oficios hórridos humanos,

que son como tizones infernales encendidos de tiempo inmemorial

por el crudo secuaz de la hogueras; amortigua, ¡oh señora!, la presteza

con que el cierzo sañudo y tan frío

bate las nuevas aras, en el humo enhiestas, de nuestro cuerpo ayer, ceniza hoy,

que ni siquiera pizca gozó alguna,

de los amos no ingas privativo

el ocio del amor y la sapiencia.

Ya descuajaringándome, ya hipando hasta las cachas de cansado ya, inmensos montes

todo el día alzando de acá para acullá de bofes voy, fuera cien mil palmos con mi

lengua, cayéndome a pedazos tal mis padres, aunque en verdad yo por mi seso raso, y

aun por lonjas y levas y mandones, que a la zaga me van dejando estable, ya a más

hasta el gollete no poder, al pie de mis hijuelas avergonzado, cual un pobre

amanuense del Perú.

Nuestro amor no está en nuestros respectivos y castos genitales, nuestro amor

tampoco en nuestra boca ni en las manos: todo nuestro amor guárdase con pálpito

bajo la sangre pura de los ojos.

Mi amor, tu amor esperan que la muerte

se robe los huesos, el diente y la uña, esperan que en el valle solamente

tus ojos y mis ojos queden juntos, mirándose ya fuera de sus órbitas,

más bien como dos astros, como uno.

¡Oh alma mía empedrada

de millares de carlos resentidos por no haber conocido el albedrío de disponer sus días

durante todo el tiempo de la vida; y ni una sola vez siquiera

poder decirse a sí mismo:

“abre la puerta del orbe

y camina como tú quieras,

por el sur o por el norte,

tras tu austro o tras tu cierzo…!”

¡Oh Hada Cibernética!,

cuándo de un soplo asolarás las lonjas, que cautivo me tienen,

y me libres al fin

para que yo entonces pueda dedicarme a buscar una mujer

dulce como el azúcar,

suave como la seda,

y comérmela en pedacitos,

y gritar después:

“¡abajo la lonja del azúcar,

abajo la lonja de la seda!”

En las vedadas aguas cristalinas

del exclusivo coto de la mente,

un buen día nadar como un delfín, guardando tras un alto promontorio la ropa protectora pieza a pieza,

en tanto entre las ondas transparentes, sumergido por vez primera a fondo sin pensar

nunca que al retorno en fin al borde de la firme superficie,

el invisible dueño del paraje

la ropa alce furioso para siempre

y cuán desguarnecido quede allí, aquel que los arneses despojóse,

para con premeditación nadar,

entre sedosas aguas, pero ajenas,

sin pez siquiera ser, ni pastor menos.